‘Hamilton’ hype highlights our transatlantic differences

written for the Financial Times, 27 January 2017

The Founding Fathers may have been American, but this week, with no apparent sense of irony, Theresa May made them British. Speaking to Republican leaders in Philadelphia, the prime minister had only praise for the signatories of the US Declaration of Independence: “For the past century, Britain and America — and the unique and special relationship that exists between us — have taken the idea conceived by those ‘fifty-six rank-and-file, ordinary citizens’, as President Reagan called them, forward.” You might have thought the Declaration of Independence was an act of secession from France.

If Mrs May’s speech was aimed at reminding America of a shared promise, it was always going to be a hard sell at home. A YouGov survey last week found 54 per cent of Britons reported that the election of Donald Trump had given them a more negative vision of the US.

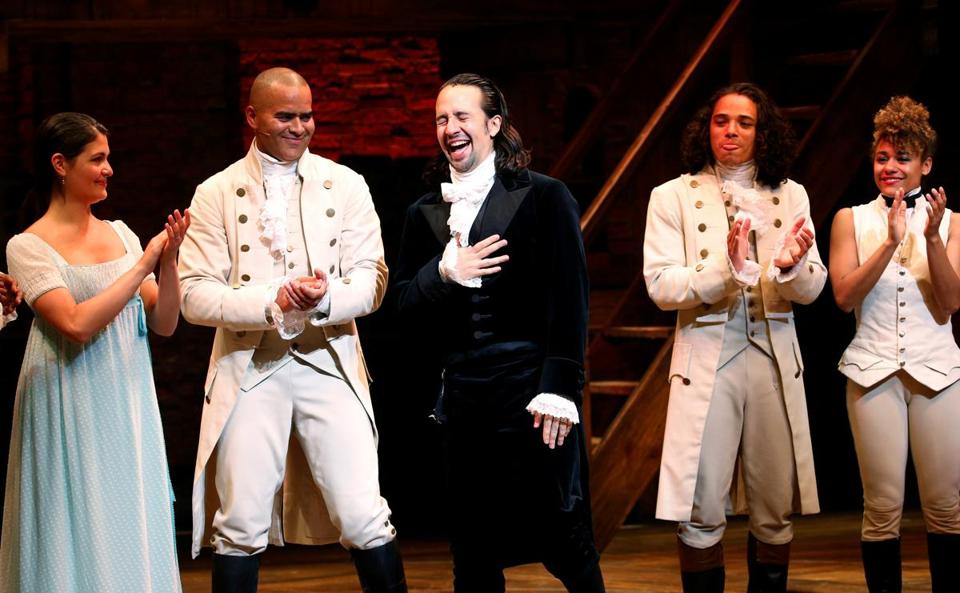

In London, however, those ‘fifty-six rank-and-file’ citizens are poised for a surge in popularity. On Monday, tickets go on general sale for November’s West End transfer of Hamilton, the record-breaking Broadway tribute to America’s first Treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton. Piqued by the show’s US success (11 Tonys, one Grammy and a Pulitzer) and that of its social media-savvy creator Lin-Manuel Miranda, Hamilton has an expectant British fan base. The US cast album has spent a year in the UK charts.

An illegitimate, penniless immigrant from the Caribbean — “the ten-dollar Founding Father without a father” — in Miranda’s musical, Hamilton’s life epitomises the American dream: “How does a bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a Scotsman . . ./Grow up to be a hero and a scholar?” This is a vision that the American left can get behind. Hamilton, we learn, is a liberal of the old school, defending civil rights and struggling against more patrician colleagues. America, he sings, is a “great unfinished symphony”. Audiences may hear the echo of Martin Luther King’s “American dream . . . a dream as yet unfulfilled”.

The musical makes even grander claims for its hero’s progressive promise. If Hamilton hadn’t been shot dead at 47, we are assured, he might have cleansed America of slavery. (The historical record shows less evidence that Hamilton ever prioritised abolitionism politically.) In one of the show’s more on-the-nose moments, his sister-in-law Angelica Schuyler pronounces, “‘We hold these truths to be self-evident/That all men are created equal’/And when I meet Thomas Jefferson I’m ‘a compel him to include women in the sequel!” This is King’s American dream, fulfilled.

To enforce the point, Hamilton’s all-American cast is non-white, with the exception of a white actor in the villainously camp, comic role of King George III. Casting announcements made on Thursday evening, just as Mrs May unveiled her own American dream in Philadelphia, suggest the London production will follow suit.

Mr Trump accused the Broadway cast of “harassing” vice-president Mike Pence after a November performance. (Nobody who attends a performance of Hamilton should expect anything other than a political lecture, albeit of superlative musical quality.) By contrast, Barack Obama praised Hamilton as “a civics lesson our kids can’t get enough of”.

In keeping with the two presidents’ relative popularity, Londoners are likely to spend this year reciting Miranda’s best lines — “Immigrants, we get the job done!” chants a triumphant Marquis de Lafayette at the Battle of Yorktown — rather than sharing supportive gifs of the Trump-May summit.

But are the Founding Fathers natural heroes for Britain? In a marked disjunction between the American and British left, Hamilton is a tribute to meritocracy. (Hamilton “Got a lot farther by working a lot harder/By being a lot smarter/By being a self-starter.”) British audiences may be less quick to lap up odes to American exceptionalism. Where other musicals have love letters, Hamilton has the Federalist Papers. The American left roots itself in a constitutional tradition; the British left feels no such obligations to the literary byproducts of late 18th century American history.

It is an odd time to be singing the virtues of the American constitution. With the challenge posed by Mr Trump, American leftists and even liberal conservatives have begun to doubt its irreducibility.

David Frum, a former George W Bush speech writer, wrote this week in The Atlantic that the presidential selection mechanism is “an 18th-century contrivance for a confederation of sovereign states, it fits ill with a modern mass-media democracy”. It would be ironic to see the constitution’s greatest-ever pop-culture advertisement become its international last stand.