Book Review – Shylock is My Name: The Merchant of Venice Retold

reviewed for The Times, 23rd January 2016

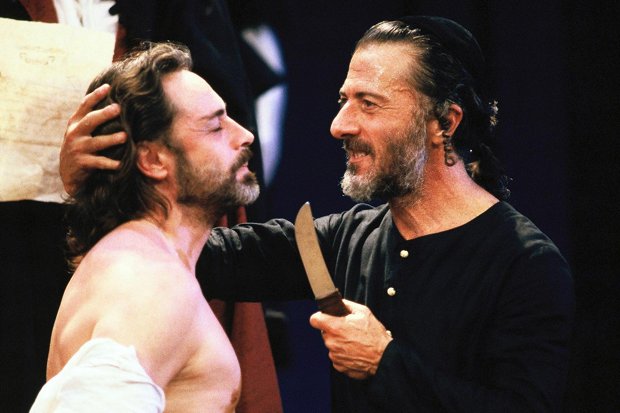

Dustin Hoffman as Shylock in Peter Hall’s 1989 production of The Merchant of Venice

Image credit: Georges de Keerle / Getty Images

Shylock is My Name: The Merchant of Venice Retold. Vintage, pp.277, £16.99, 9781781090282

by Howard Jacobson

If you want to safeguard against anyone taking your anti-heroine seriously, name her “Anna Livia Plurabelle Cleopatra A Thing of Beauty Is A Joy Forever Christine Shalcross”. There’s always the chance that no one will be able to take the rest of your novel seriously either, but perhaps that feels less of a worry if you’re Howard Jacobson, a Booker prizewinner on his 14th novel.

In this retelling of The Merchant of Venice, the stuff of Jacobson’s better work — the neurotic intellectualism, the long train of self-questioning doppelgängers — leaves vestigial traces. Structured around a set of dialogues between two Jewish fathers, Shylock is My Name has much to tell us about loss, identity and modern antisemitism. It wouldn’t have made a bad series of columns in The Independent.

Crashing into these meditations with all the sensitivity of an iceberg, however, is a crude retelling of The Merchant of Venice’s comic plot, based in Ms Shalcross’s boudoir. As Jacobson leads us through a world of surgically augmented heiresses and fashionably antisemitic footballers, Shylock Is My Name too often feels as tacky and tawdry as the heartless Cheshire society it depicts.

It’s an article of faith, nowadays, to point out that in Shakespeare’s original, nobody is very nice. Bassanio wins the heiress Portia by guessing that her portrait lies within a casket of lead, rather than one of gold or silver. However, if he’s good at pretending he’s not motivated by money, he still treats love like a private equity venture, raising capital for an impressive courtship by borrowing from melancholic Antonio. “We are the Jasons, we have won the fleece!” boasts his friend Gratiano when they finally land Portia’s gilded trust fund.

Meanwhile, these Christians borrow more money from the Jewish Shylock, insult his faith and collude in the elopement, ducats and all, of his daughter Jessica. No wonder, modern directors have concluded, that Shylock hardens into a man determined to extract his pound of flesh.

Shylock haunts Anglo-Jewish literature. In Jacobson’s story, he’s conjured into being in a Manchester cemetery, the imaginary friend of Simon Strulovitch, who needs someone to talk to about his acquisitive business ventures, local enemies and culturally deaf daughter. (“Hers was the first generation, Strulovitch thought, who came into the world without memory.”) Clearly, Simon is an alternative Shylock, incapable of learning from his ghostly counsellor’s mistakes.

But he’s also by turns Othello, loving his daughter not wisely but too well, or Malvolio, swearing to be revenged upon the whole pack of us, or even Lear, impotent with rage, doing he knows not what. To be a hundred souls fighting in one is, Jacobson suggests, something essential to being Jewish, a supplicant invited, uniquely among faiths, to answer back to his God. Simon’s debates with Shylock, snapshots of a man haranguing his literary Creator, are the heart of this book, knowing and humane.

There’s no such humanity, however, in the paper-thin caricatures that populate the rest of Jacobson’s novel. In The Merchant of Venice, even while Shakespeare’s gentiles may lack gentleness, they rarely lack for lyricism. His Portia is more than capable of navigating the complex hypocrisies of desire and desirability, fisking Bassanio over whether his lust for her golden hair is more or less shallow than others’ coveting her golden coins.

By contrast, Jacobson’s extravagantly named starlet (“Plury” for short) seems to have pranced straight from The Real Housewives of Cheshire (or The Kitchen Counsellor, her dating-based reality TV show). The queen bee of Cheshire’s Golden Triangle (geddit?), she’s incapable of spotting who’s really after her money. Even Portia’s most eloquent intervention, her paean to mercy, is placed here in the mouth of Shylock, who recites it as she and her dumbfounded cronies look on.

Plury and Strulovitch cross paths when she encourages his daughter, a 16-year-old performance artist, to shack up with Gratan, an oafish minor footballer known for giving what looks like a “quenelle” salute on the pitch. (“Name a single occasion on which he’d been booked for fouling a Jewish player”: the latest plausible deniability in antisemitic circles). Jacobson is good on the creeping acceptability of “Jewepithets” and racism’s slippery masks. Plury’s friend D’Anton, a gaudy fop, opposes Strulovitch’s plans for a museum of Jewish art for aesthetic reasons, and just happens to also encourage a local boycott of a global firm with Israeli dealings.

Strulovitch knows that to confront antisemitism is to confirm it: that his rage and anger only appear as paranoia. (“How, sociopathically, had it become a foul to cry foul?”) But he’s denied tragic stature by Jacobson. The revenge he seeks to exact, first on Gratan, then on D’Anton, is comic to the point of incredulity — much ado about foreskins, by the poor man’s Philip Roth.

The modern problem of Shakespeare’s play is that it presents itself as comedy: most directors sidestep it by switching genre wholesale, masking those old, entrenched traces of the pantomime Jew as deserving dope. But the hardest task Jacobson has set himself is not to tackle antisemitism but to haul The Merchant of Venice by the golden hair back to the sphere of crassest groundling comedy.

Jacobson knows his text — the play’s sensitivity to music, infecting ears across cultures and through closed windows, is well explored. But The Merchant of Venice was not Jacobson’s first choice to adapt for Hogarth’s series of novelisations of Shakespearean plays. He wanted Hamlet, but Hogarth insisted on Merchant: who else to tackle Shylock but Britain’s resident grumpy old man of Jewish letters?

So there is something wearily predictable about Jacobson’s shtick, weighed down by a lukewarm fidelity to Shakespeare’s plot. But perhaps the imaginative failure is Hogarth’s. There are several younger, talented Jewish writers who deserve a chance to tackle Shylock. This was their missed opportunity.