Doctor Faustus, Shakespeare’s Globe

reviewed for The Spectator, 28 June 2011

The text that codified the old legend of the learned man who sells his soul to the devil, Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus is one of the most influential plays in English history. It’s also one of the worst, from the point of view of the director.

Scenes of intense religious struggle are intercut with the crudest of groundling comedy skits, in the most incongruous of juxtapositions. It may be Marlowe’s way of emphasizing that, under his silks, Faustus is as ineffectual and decayed as the world he inhabits, but it doesn’t do much for narrative flow. And that’s before you get to the serious problems with the pacing of the play’s theological climax, or the 16th Century political lampoons of characters that flit in and out of the action before we’ve even had time to identify them.

But all this is why Matthew Dunster’s imaginative staging at Shakespeare’s Globe should be welcomed. For once, we have a Faustus that is coherent and watchable, even while festooned with the type of garish spectacle that made this uneven play a hit with Early Modern Londoners. You’re unlikely to see a production in which the raucous tavern scenes are so deftly brought into line with the main plot.

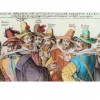

Much of this is due to the power of Steve Tiplady’s anarchic puppetry – there’s a cold thrill that unfurls over the pit as oafs and clowns find themselves under absurdist attack from their own bodies, only to be exposed as playthings for the same menacing painted devils that we see massing for the damnation of Faustus himself. Yet, despite the aesthetic clarity of Tiplady’s puppets, from the luxury seats of the middle circle even the largest set pieces couldn’t help but feel a little small. This may be one of those few productions at the Globe that is better experienced from up close.

Paul Hilton nails the cynicism and despair of Faustus, a man unable to understand the point of ‘contrition, prayer, repentance’ because he believes himself damned long before Mephistopheles even appears on the scene. Faustus’s atheism stems not from a disbelief in God Himself – after all, the gilded angels and devils dancing before his eyes should be proof enough – but from a conviction that God is a tyrant, a conviction given plenty of fuel in the 16th Century by the emergence of High Calvinism. Hence Hilton’s bitter, riveting ‘God? – He loves thee not!’

Nonetheless, in Hilton’s underplayed performance, it can be hard to pick out exactly what motivates Faustus. Contemplating his achievements as a medical doctor, Hilton lays stress on Faustus’ desire ‘to be eternised for some wondrous cure’, before Arthur Darvill’s Mephistopheles foregrounds his promise ‘doubt not Faustus but to be renowned and more frequented… than hereforeto the Delphic Oracle’.

So we think we’re about to watch a morality tale about the supposedly modern desire for celebrity, only for Hilton to unveil a slew of diverse vices, sins of the flesh being not least among them. He’s helped by the best parade of the seven deadly sins you’re likely to see in a while – including a stand-out cameo from Sarita Piotrowski as Pride – mundanely human in their bourgeois clothes, yet portentously demonic under the harsh black and scarlet colour scheme.

It’s these designs by Paul Wills that help make Faustus’ desires so seductive, despite the underlying grotesquerie on show. After Felix Scott’s forthright, articulate delivery of the prologue, the production opens onto a chorus of smoothly choreographed scholars, clad in black period garb with the addition of sunglasses. Rarely has scholarship rocked the sexy-Mafia look so well.

In a deft trick, they rhythmically open and close the geometric illustrations to books of magic – we are seduced by the very paraphanalia of Renaissance hermeticism before we know it. Meanwhile, Jules Maxwell’s music hints at a perfect combination of the martial and the sacred – we’re not as far away from the masculinity of Tamburlaine as the chorus suggests.

So it’s a shame that Dunster simplifies the intellectualism of the text ever more as his production wheels towards its close; in the second act, it feels like a scramble to throw ballast off a ship as it races towards the shore. The first act shows an understanding of the power Latin incantations still have in our culture – ritually, Faustus recites his scholarly statements while, in almost comic counterpoint, his chorus provides the audience with a translation.

But when Faustus grapples with religion again, unable to beg for salvation in the play’s final scenes, this production seems to forget that Latin can be a spiritual language as well as a magical one. It’s hard to forgive the omission of Faustus’ prayer on his night with Helen – currite, currite lente noctis equi (pace, pace slowly, you horses of the night) – in which Faustus ironically appropriates the words of Ovid’s priapic lover, while grasping at an echo of English Catholic Latinity.

It’s not the only example of such simplification towards the play’s close. The ensemble’s mincing, sniveling attempts at mocking the Tudor aristocracy make the second act’s comedy painful to watch, where the first act’s back-and-forth between servants Pearce Quigley and Richard Clews (the latter looking like Eastenders’ Nick Cotton trying to be Johnny Hallyday) is a joy. Meanwhile, Darvill’s impish Mephistopheles manages to be both ethereal and sly, but never quite manages the gravitas needed to really intrigue us.

Nonetheless, the Dunster’s energetic production deserves to be a success. Hilton’s impressive performance provides the underpinning of an unusually acute analysis of the nature of damnation. And for audiences often scared by Marlowe, the Globe has pulled off a superbly accessible introduction to one of the English canon’s most challenging plays.