Terminus, Young Vic

reviewed for The Spectator, 13 April 2011

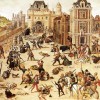

No one can accurately imagine Hell. In Terminus, a magical paean to the art of storytelling, playwright Mark O’Rowe wisely does not try. The one soul in his universe who does manage to escape the place, finds himself, like Old Hamlet, unable to unfold its horrors to the youthful melancholic he encounters in a run-down corner of Dublin. But Miltonic questions of salvation, punishment and survival are infused through every phrase of the language his characters inhabit.

Hell, or its earthly echo, an inner-city sink estate, may be inescapable for some, but the characters of Terminus are indefatigable in the search for loopholes to salvation – hence the intoxicating bravado of one claim, that ‘I’ve heard tell that even the Devil remembered Heaven, after he fell.’ It is the poetic force of Terminus that lifts it into the ranks of the extraordinary.

The performance consists of interweaving dramatic monologues by three characters, each of whom narrate their experience of the same troubled night in the city centre. But where some monologue dramas might lack dramatic detail, in Terminus the gap is filled by the rapid movement of the language. This is dazzling poetry, full of surprises, with changes in rhythm or rhyme scheme as ready to leap out at us as a character is to change direction in her winding tale, or to relate an impulsive change of plan. It’s utterly beautiful.

The script is laid out as prose – but this is still verse propelled by a commanding beat, loaded with subtly slanting internal rhyme. It makes for gripping storytelling. There is a roughness to this magic that comes from its close relation to Beat poetry – and it is this abrasive theatricality that allows O’Rowe’s gritty, painful vision of Dublin to share space with the world of nurturing angels and repentant demons. Generally, the cast rise to the challenge of this linguistic adventure admirably. Declan Conlon is outstanding as a man consumed by his desire for sexual prowess, half wide-boy, half Count Dracula. Utterly in command of the poetry, utterly in control of the audience, his is a magnificent performance.

The always impressive Olwen Fouéré is equally captivating, in a more controlled role as a Samaritan counsellor drawn into a vigilante hunt to prevent a back alley abortion. Catherine Walker struggles more with the constraints of monologue, but what she lacks in range of gesture, she makes up for in the elegance of her vocal delivery. A plot twist near the end of the piece may hint at an explanation for the permanent crouch of her body, but barely makes it less distracting. And the vagueness of this point is a result of the most frustrating aspect of this piece.

In a piece deeply concerned with the dynamics of storytelling – one character trades life stories with a demon like emotional currency, Fouéré’s dayjob consists of listening to stories on the telephone – it is implied that most of these characters will not actually get a chance to tell theirs. The metaphysical structure of O’Rowe’s universe – not to be revealed to readers who have yet to see the piece – does not seem to allow for the very act of storytelling we are witnessing by attending the theatre. It leaves these

stories in limbo, a place ill-fitting their poetic dignity.