Cyrano de Bergerac, Royal Theatre, Northampton

reviewed for The Times, 10 April 2015

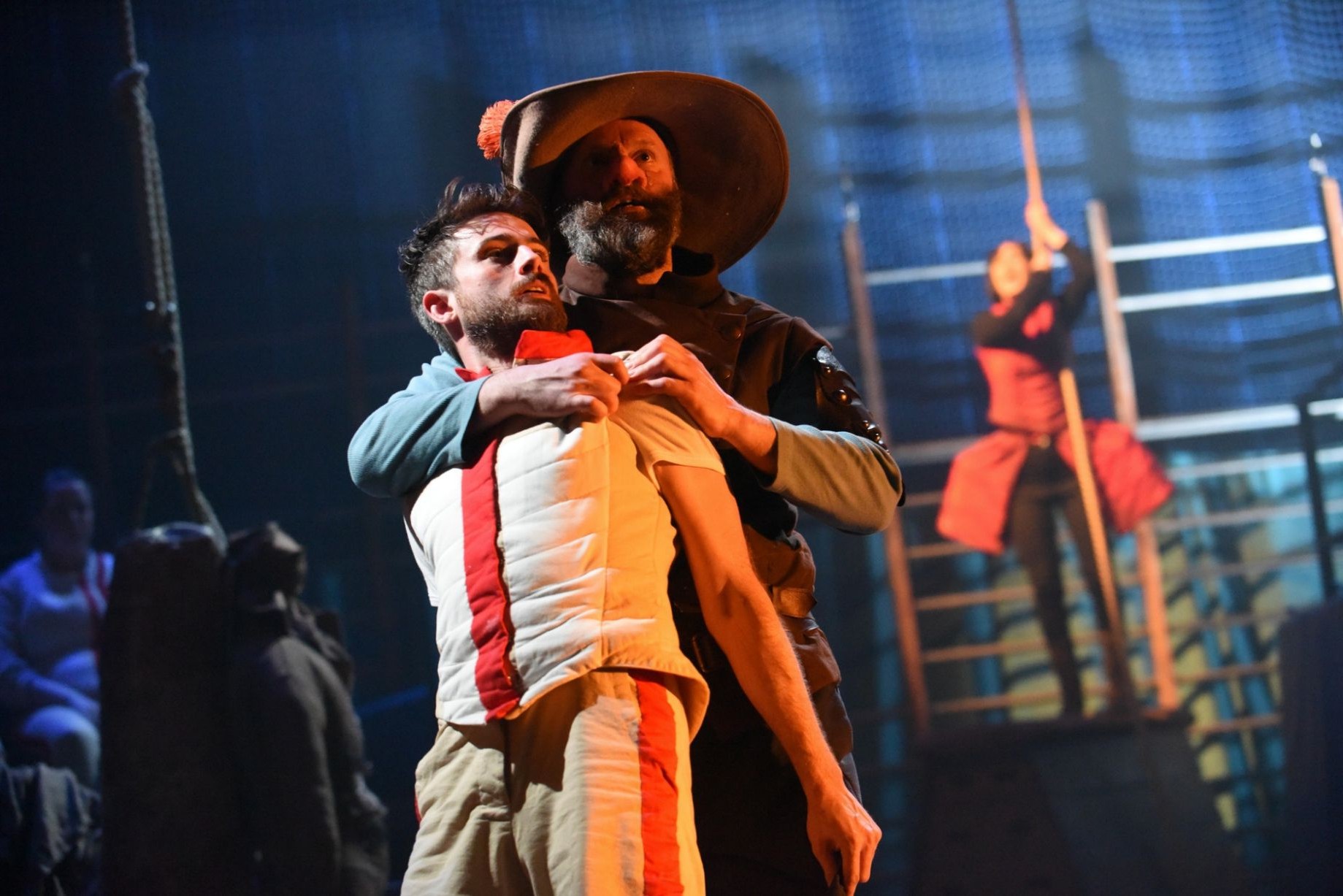

Nigel Barett and Chris Jared

![]()

Forget swashbuckle. Forget, even, panache. True, Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac, the tale of Louis XIII’s most dashing swordsman, is a celebration of the high style. When written in 1897, Rostand’s “heroic comedy in verse” was already a period drama. So Rostand takes us back, past the Industrialists, to the era of The Three Musketeers (D’Artagnan himself has a cameo).

Rostand was never subtle about using his protagonist as a literary proxy — when we first meet Cyrano, he’s shutting down a theatre at rapier point for offending his taste — and by showcasing the neoclassical wit of his hero, all Alexandrine couplets and verbal grace notes, he threw down the gauntlet to the emerging realism of Ibsen and Strindberg.

Yet in its lament for the bravest of cowards, a man who leaps at the chance to duel a hundred assassins in one sitting but can’t admit his feelings to the woman he loves, this is also a story about weakness. After composing love letters to Roxane and letting another man sign them, he’s in hiding for the first time in his life. At the centre of Lorne Campbell’s production for Northern Stage, Nigel Barrett understands this tension intuitively: Barrett’s Cyrano is hypnotically understated, gently generous, a friend to everyone except himself.

He mentors love-rival Christian (Chris Jared, bland as a pasty boyband) not, one senses, because Cath Whitefield’s archly gamine Roxane asks him. Rather, nurturing virtue in others is how this Cyrano has always fed his self-contempt, an ethical dysmorphia that goes far beyond a bulbous nose. Yet in the hurly-burly of Campbell’s direction, a mess of malfunctioning metatheatrical tricks, Barrett’s quiet vulnerability is all too easily drowned out.

To be fair, a text with a cast of 50 would faze most directors. Campbell’s approach is to give Rostand the Pirandello treatment: we start by watching ten actors warm up in a ghostly gymnasium, dressed as acrobatic fencers, which gives them the air of a hit squad of lethal harlequins. From then on, it’s a mishmash of genres, although epic appears to be the descriptor adopted by the box office to justify the 200-minute running time. There’s even the odd rap — and in a play where verbosity is virtue, it’s intriguing to think what adaptation into a full-scale rap-opera would look like. Yet there’s no such commitment to any one idea here. More’s the pity.